Plato’s attitude towards knowledge of the sensible world is the subject of divergent assessments. His influence has been mostly judged negatively, since the thesis he supports – namely, that true reality is that of intelligible forms, of which sensible forms are only images – would lead more towards metaphysics, if not religious mysticism, than towards the study of natural phenomena. From another point of view, however, it may seem that Plato’s approach anticipates modern science in that he takes mathematics as a model of knowledge and describes in mathematical terms the stability that manifests itself in the sensible world. If we accept that there are different levels of reality and that true reality is that of intelligible forms, it follows that knowledge of sensible things cannot be considered science in the strict sense of the term. Drawing on images of the sensible reality rather than the intelligible reality, it can only achieve verisimilitude, while the true will always elude it. Its status therefore remains inferior, despite the fact that Plato devotes most of his work to discussing the sensible reality.

On the basis of these considerations, we must therefore define Plato’s attitude towards the knowledge of his time (mathematics, medicine, etc.): was he an enlightened amateur or a true connoisseur? In this regard, an important development in Platonic thought must first be clarified. At first, following Socrates, he identified a rigorous model of approach to knowledge of the sensible world in the téchnai (the term téchnē in ancient Greek designates a wide variety of skills and abilities, ranging from the figurative arts to rhetoric, from medicine and navigation to architecture, and also includes the work of blacksmiths, carpenters, and even shoemakers). These are skills and practices that, in one way or another, have always existed and are characterized by their specialization; in this field, no expert claims total knowledge. A téchnē implies the control of specialized knowledge, which seeks to dominate its field of experience through rational procedures. These procedures can be publicly described and must allow effective results to be obtained within their limits. A téchnē is capable of claiming true autonomy in that it has its own domain, procedures, and results. Furthermore, a téchnē can be transmitted and taught, which implies an accumulation of knowledge; finally, it confers social dignity on those who practice it.

In Plato’s early writings, the reference to téchnai has two main functions: it allows for effective opposition to any kind of false knowledge and proposes models of “know-how”. Every téchnē involves an activity (érgon) that may consist in the production of an object (e.g., a flute, a boat), involve the use of these objects (music, navigation), or even relate to the care (therapeía) of certain natural objects (fields, livestock, human bodies). Within the limits of its own field, téchnē has full knowledge of the rational procedures of its intervention, procedures that it is able to transmit through teaching; in this perspective, it has a normative character and claims – in relation to its object – an effectiveness (dýnamis) of intervention. Téchnai can therefore be proposed as a model for ethics and politics because they are always a “know-how” and a “can-do”.

That said, two problems arise that call into question the use of téchnē as a model of knowledge: on the one hand, the objects of all téchnai depend on the sensible world, which is subject to incessant change and, as such, cannot become the object of thought and language; on the other hand, every téchnē is based on the pursuit of the interest of the person who practices it, unlike a number of other forms of knowledge, such as astronomy, where interest does not come into play. This is why Plato, without completely abandoning what the téchnai had given him, turned after the Meno to another paradigm: mathematics. The sensible reality must be endowed with true stability if it is to be intellectually apprehended and spoken about, and only mathematics enables human beings to apprehend and describe this stability. Pure mathematics, considered an object of study in itself, therefore allows the soul to escape the sensible, even if in the Greek practice construction (with ruler and compass) was given precedence over calculation. The ideal nature of mathematics allows Plato to understand the necessity of the existence of intelligible forms, of which sensible forms are nothing more than images.

But not only that: in fact, insofar as it manifests the symmetry that ensures true stability to the realities perceived by the senses, it appears as a trace of the intelligible in the sensible. All that human beings can do is observe and describe this stability within the framework of the various forms of knowledge: cosmology (or astronomy), physics, chemistry, biology, medicine, psychology (normal and pathological), botany, geography, and history. It is useful to remember, however, that this inventory of different forms of knowledge uses modern terms that are not found in Plato to designate established forms of knowledge, except perhaps for astronomy and medicine. In fact, there is no term in Greek that corresponds to “knowledge” as distinct from “science” (in Greek epistḗmē, a term that Plato reserves for knowledge of true realities, represented by intelligible forms).

Plato therefore admits the existence of separate realities in order to allow sensible things, which are copies of them, to become objects of knowledge and discourse; he also approaches all types of knowledge of the sensible world with a rigor and consistency that are primarily, directly or indirectly, characteristic of mathematics.

The philosophical doctrine proposed by Plato is characterized by a double reversal. First of all, the world of things perceived by the senses is nothing but a copy of intelligible forms (or Ideas) which, as models of sensible things, constitute true reality; unlike sensible things, intelligible forms possess their principle of existence in themselves. Furthermore, man cannot be reduced to the body, and his true identity coincides with what we designate by the term “soul”, whatever the definition proposed for this entity which accounts – not only in man, but also in the Universe as a whole – for every movement, whether material (growth, local motion, etc.) or spiritual (feelings, sensory perception, intellectual knowledge, etc.). It is this double reversal, this double transcendence, which, throughout the history of Western philosophy, has made it possible to define the specificity of Platonism. The hypothesis of the existence of intelligible forms, which Plato never defines and whose negative features he merely mentions, allows the philosopher to establish an ethics, a theory of knowledge, and an ontology.

Faced with the confusion reigning in Athens, when the political order of the city collapsed under the blows of its adversaries and citizens made contradictory statements about common values, Plato, while seeking to continue Socrates’ work, attempted to propose a different political discourse: a political discourse based on absolutely certain moral principles that could serve to transform cities. This explains why the first dialogues deal with ethical or political issues. It is a question of defining the essential virtues of the perfect citizen; this requirement implies the existence of absolute norms which, in order to serve as reference points for guiding and evaluating human conduct, must not depend either on tradition (such as those transmitted by poets) or on arbitrary conventions (as the Sophists claim).

But this hypothesis, which makes an ethical system possible, refers back to the epistemological sphere, as can be seen in the Meno. In order to discover and learn the absolute norms on which ethics is based – which, as such, cannot be found in the sensible world – we must hypothesize the existence of a faculty distinct from opinion: the intellect. Now, the distinction between intellect and opinion entails a distinction between their respective objects: if the domain of opinion is the sensible things immersed in becoming, on which it formulates judgments, the intellect can grasp immutable and absolute realities. In short, in order to legitimize the processes of knowledge presupposed by ethical requirements, Plato is led to hypothesize the existence of those realities that are intelligible forms. From this perspective, the hypothesis of the existence of a world of intelligible forms appears to be an effective expedient, but one with an exclusively practical function.

Intelligible forms certainly account for the processes of intellectual knowledge; however, sensible reality does not depend on these processes of knowledge. If, in the sensible world, objects and their characteristics are reduced to the transitory results of composite movements, regardless of the necessities of ethics and epistemology, the hypothesis of the existence of an ontological foundation is necessary in order to arrive at an explanation of sensible phenomena which, left to themselves, would otherwise dissolve into Chaos (a hypothesis considered in Timaeus, 52 a–b). Such sensible phenomena can be known and spoken of only insofar as they exhibit a certain stability, that which is ensured by their participation in the intelligible. The demiurge, fixing his gaze on the intelligible forms in the creation of the universe, guarantees this stability. He thus makes possible, in the city, the existence of norms useful for guiding human conduct, both individual and collective, since he resolves – at least in a mythical context – the problem of the participation of sensible things in intelligible forms. Ethics and politics require the existence of a certain order, a certain permanence in the sensible world; this must have been Plato’s intention in writing the Timaeus, which appears in some ways as the conclusion of a process whose essential stages are the Meno, the Phaedo, the Republic, and the Phaedrus.

This division of reality into models, which constitute true reality, and copies, which involve only a derivative reality, implies a strictly parallel distinction on the level of knowledge and discourse. In this regard, this passage from the Timaeus is eloquent: “Thus we must distinguish between the image and its model, for discourses have a certain kinship with the object they interpret: and therefore discourse about what is stable, fixed in itself, luminous to the intellect, is itself fixed and unshakeable and, as far as possible, must be irrefutable and unshakeable, and none of these conditions must be lacking. As for discourse about what that model represents and is its image, such discourse will be plausible and related to the first, since truth is to belief as essence is to existence” (ibid., 29 b–c). The intellect, whose object is intelligible forms, is therefore opposed to true opinion, whose object is sensible things perceived by the body; and to this epistemological opposition there is added another, sociological: “it must be added that the intellect is proper to the gods and to a small number of men” (ibid., 51 e). This small number of men are obviously philosophers.

Science (epistḗmē) has as its object true reality, the model of all sensible reality, which is not apprehended by the senses but by the intellect (noús). The knowledge that results from this, and the discourse that transmits this knowledge, are characterized by certainty and reserved for the philosopher. On the other hand, true opinion (alēthḗs dóxa) has as its object copies of true reality. These derived realities are perceived by sensation (aísthēsis) which, as we shall see, goes back through reminiscence to the rational species of the soul and to the intelligible. However, the knowledge that results from sensation cannot attain certainty, since its object is a changing image. The same applies to the discourse that transmits this knowledge, which Plato qualifies as “plausible myth” (eikós mŷthos) or “plausible discourse” (eikós lógos) precisely because, since it deals with images and not with the true reality that constitutes their model, it cannot be true in the full sense of the word.

This parallelism between reality, knowledge, and discourse is illustrated in The Republic by the allegory of the line. The line has two main sections, one representing what pertains to the senses, the other to the intellect: “Now take a line divided into two unequal parts (if we accept the lesson ‘ánisa’) and divide each part again in the same proportion, that is, the part of the visible species (horōménou) and the part of the intelligible species (noouménou)” (Respublica, VI, 509 e). The sensible is designated, in a kind of synecdoche, as pertaining only to sight: the other senses (hearing, taste, smell, and touch) are not even mentioned; moreover, the intellect is evoked only by a verb (noeîn) which in Homer (Iliad, III, 374, 396; XV, 422; XXIV, 294) and in Hesiod (Theogonia, 878) designated sensory vision, as Aristotle does not fail to point out in De Anima (III, 3, 427 a 6 ff.). Plato reveals himself to be the heir to this tradition, since for him the object of the intellect is Form, in Greek eîdos or ‘idea’ (a term derived from a root *weid- that has produced several words related to sight).

The description of the lower section of the line (Respublica, VI, 509 e – 510 a), which corresponds to the sensible and comprises two parts (one representing sensible things and the other the images of these things), also introduces some visual metaphors. In both cases, the notion of perspicuity intervenes, referring to realities that are distinct only in terms of their ontological status: on the one hand, sensible things and, on the other, their images. While the lower part of the lower section – images, reflections, etc. – is described exhaustively, the other part is not subject to a complete inventory; only living beings and man-made artifacts are considered. The upper section of the line also has two parts: one corresponding to the domain of mathematics, the other to that of Ideas, or intelligible forms.

Plato makes no mention of the ontological status of numbers and figures. He merely formulates two criticisms: geometers make use of material figures and, above all, remain at the level of hypotheses (ibid., 511 a–b). The fact that they use images draws mathematics towards the sensible side; however, there is something more serious. The deductive method takes as its starting points assumptions, hypotheses, which, considered in themselves, are not susceptible to proof: how, then, can they be endowed with evidence? The evidence sought cannot be discursive, since it lies at the origin – and therefore outside – of any deduction; such evidence can only be intuitive and, since it does not concern the sensible, can only be produced by an intuition of an intelligible order. Hence the need, faced by Plato, to introduce the doctrine of Ideas, which, being situated beyond principles, guarantee their validity.

Even if it is not possible to attribute a specific status to mathematical or geometric realities as such (each of them has, however, an Idea that corresponds to it: for example, that of Two or that of the Circle), it is necessary to acknowledge their essential role in mediating between the sensible and the intelligible. The study of mathematics therefore allows the soul to ascend from the sensible to the intelligible and to ensure the presence of the intelligible in the sensible.

Ideas are the object of dialectic, which, through the process of “reunion”, first ascends from Idea to Idea towards the Good, and then, through the process of “division”, descends from Idea to Idea to reach a definition, always remaining in the realm of the intelligible (ibid., 511 b–c). Dialectic, understood in this way, therefore describes the relationships between Ideas and allows us, in some way, to draw up a map of the intelligible world. However, it presupposes intuitive evidence, that of reason (noús), which, applied to Ideas and ultimately to the Good, serves as the foundation for the deductive process and guarantees the validity of principles (which, without the hypothesis of the existence of Ideas, would remain unfounded).

The section on diánoia poses some problems, since it seems that no particular reality corresponds specifically to this cognitive faculty. In the history of Platonism, various interpretations have been put forward to attribute a specific object to diánoia: in particular, it was believed to be number, with which the soul was identified, since the soul and number appeared as two intermediate realities between the sensible and the intelligible. But, as we shall see, this identification seems highly unlikely: on the one hand, because diánoia is only one of the many faculties of the soul; on the other, because, like the soul, it guarantees not only the influence of mathematics on reality but also the existence and persistence of movement. The domain of diánoia, especially in the Republic, is equivalent to that of deduction, assimilated to a formal system in which, starting from propositions considered valid a priori, one seeks to deduce a set of true propositions by applying a few rules of inference that are not numerous and are accepted by all.

Mathematics plays a key role in that it has two inseparable sides, like a coin: one side is oriented toward the intelligible, which it allows us to tap into, and the other is oriented toward the sensible, where it represents the “traces of the intelligible.” In fact, it allows us to explain why, despite the constant change to which it is subject, the sensible gives rise to knowledge and discourse endowed with a certain universality, a certain permanence. At this level, mathematics intervenes in all domains of knowledge, as we will try to show despite the difficulty of the task: in Greek, the various fields of knowledge do not have specific names (apart from astronomy and medicine), which makes it necessary to use modern terms to refer to them; furthermore, they are neither well recognized nor accurately defined, and do not constitute a system, as is the case today. In the following discussion, we will therefore have to take into account this anachronism, which is nevertheless considered necessary for the interpretation proposed (which is based on solid textual evidence).

After demonstrating, in the Republic (II, 372 d–IV, 427 c), the need for a group of warriors from among whom those who will become philosophers and rule the city will be selected, Socrates describes to Glaucon the educational program that will serve to train these philosophers: to train warriors, they will first be introduced to mathematics, whose different branches are reviewed. The long passage that refers to this question has a peculiarity: while Glaucon tries to highlight what, in each case, could be of practical use to a warrior, Socrates insists on the abstract nature of every branch of mathematics, even though he is ready to acknowledge (525 b) that mathematics can be useful to warriors.

How can we train these philosopher-leaders who will have to detach themselves from the darkness of the sensible world and advance towards the light of the intelligible? To this end, we cannot rely on traditional education based on gymnastics and music (understood in the broad sense as everything that pertains to the Muses). Gymnastics is clearly incapable of escaping the sensible world, since it is primarily concerned with the body; the same is true of music, considering that harmony and rhythm relate to hearing and are usually imposed from outside through habit. The other arts have already been rejected as mechanical (VI, 495 d); it is therefore only with arithmetic (522 c–526 c) that we begin to learn something superior to the sensible.

Every sensory perception has the effect of arousing the sensory perception of its opposite. And the mind cannot be aware of the unity and plurality that resides in diversity until sensation has provided it with information about the contrary attributes of the same object. Even if this awareness of unity remains rudimentary, it is an act of pure intellect, an act which, when aroused in us by the study of numbers, becomes an incomparable tool for awakening thought. Arithmetic is therefore the first step towards higher education.

Geometry is also absolutely essential for access to higher education (526 c–527 c): in fact, although hidden by the use of a name that refers to a practical application – that of measuring (metría, from métron, measure) the Earth (geō, from gaîa, earth) – its true purpose, at least in Socrates’ opinion, is to arrive at abstract, universal, and even, one might say, eternal results. Furthermore, according to Plato, experience shows that if arithmetic makes the mind more agile, geometry educates it.

Socrates points out that there is a branch of geometry that is greatly neglected and should be given primary importance. Geometry is generally understood as plane geometry, but we must also consider the geometry of three-dimensional space: the geometry of solids, or stereometry (527 d–528 e). This is in fact required in astronomy, as the science of solids in motion. Although it is still ‘in its infancy’, this intermediate science needs to be studied in greater depth, but it is so difficult that its development depends exclusively on the fascination it is able to exert on the mind.

As for the geometry of bodies in motion, which, as just mentioned, is of interest to astronomy (529 a–530 c), while Glaucon praises the contemplation of the starry sky for its practical usefulness alone and not as a way of rising from the sensible to the intelligible, Socrates replies that the mind can look down even if its gaze is turned upwards, if it is content to observe without seeking to rise towards universal truths. The sky appears as an immense moving picture. However, just like geometry, astronomy must go beyond phenomena to determine the general principles that govern the movement of solids; it must therefore leave aside the contemplation of the sky to focus on the real problems, which are of a mathematical nature.

Finally, the theory of music (a field of knowledge that, at first, presents nothing obvious to Glaucon) can be elevated not only above the disputes between musicians, but also beyond the limits imposed on it by the Pythagoreans, who were interested in nothing but harmonies perceptible to the ear. Those who want to become philosophers must rise to the universal and abstract contemplation of harmonic relationships in themselves – as we see in the Timaeus – which explain the regularity of the movements of celestial bodies that emit no sound; hence the importance of harmony (530 c–531 c).

Thus freed from empiricism, all this mathematical knowledge is raised to a level where it can be considered in relation to each other; then it can truly become the prelude (but no more than that) to dialectic, the study of true realities by pure thought. Only reason, even when using hypotheses within the framework of specialized knowledge, can go beyond them and separate itself from them; therefore, it is not diánoia, but dialectic that can learn the Ideas and reach the Good. Ideas, which constitute true reality, are not perceptible and do not depend on higher principles. For Plato, science (epistḗmē), that is, dialectic understood in the sense it has in the Republic, arrives at certainty because it leads to the contemplation of Ideas that represent true reality, grasped in an act of purely intellectual intuition.

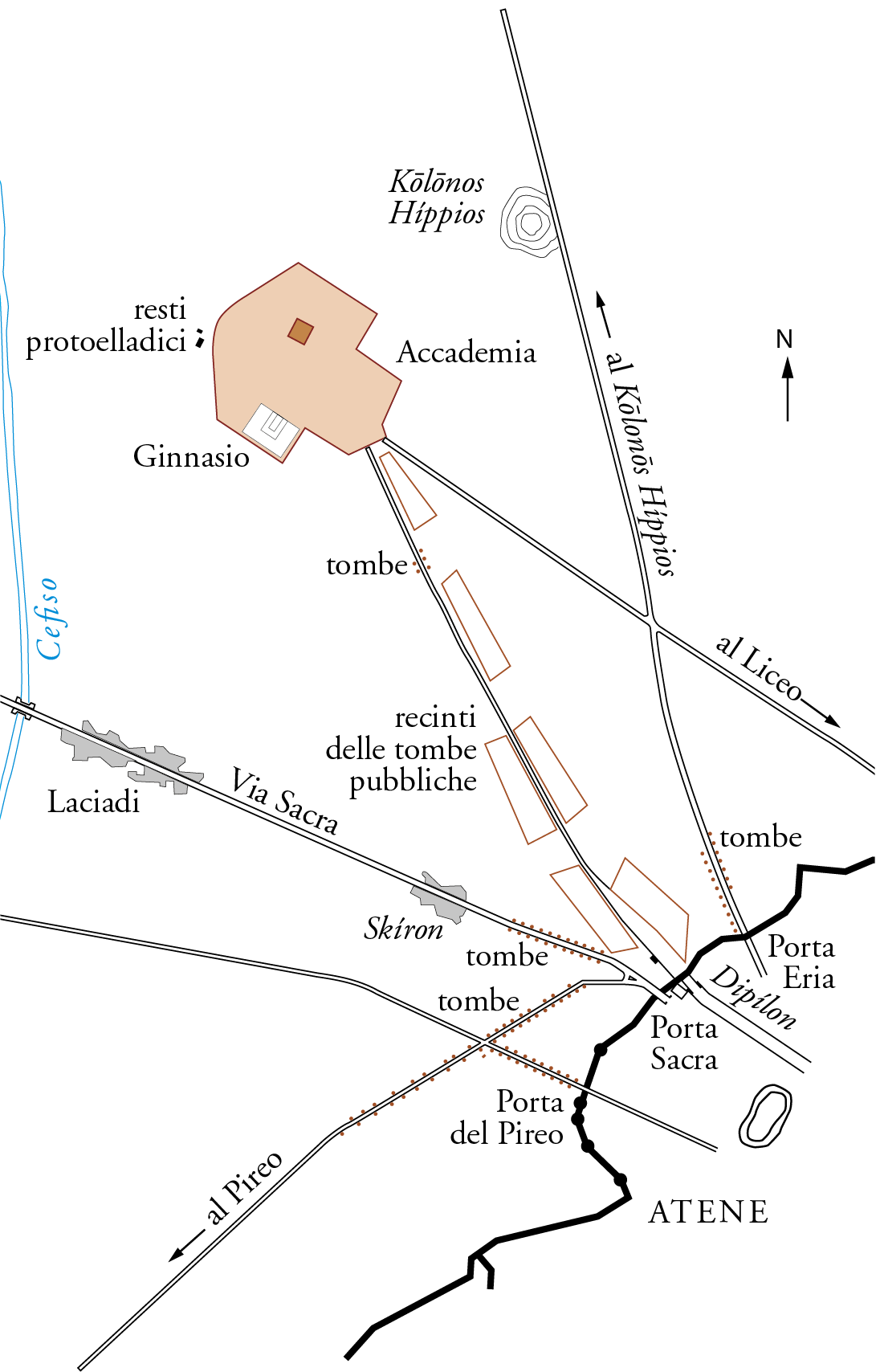

In the Timaeus, Plato develops a cosmology proposing a simple but coherent and rigorous representation of the universe, whose properties appear as logically deduced consequences of a limited set of assumptions (even if in this dialogue they remain implicit or poorly explained). The Timaeus also appears to be the first cosmology in which the description of the universe is conducted with the aid of mathematics, and not only of ordinary language (as will be the case with Aristotle, who, especially in De caelo and Physics, will never cease to criticize this mathematization of the universe undertaken by Plato). However, and this is where the Timaeus anchors itself in tradition through a myth, Plato’s description of the universe remains inseparable from a description of the origin of man and also of the origin of society, as illustrated by the myth of Atlantis, summarized at the beginning of the dialogue and narrated in the Critias.

For Plato, a cosmology that aims to offer a simple representation of the universe must be able to answer two questions: under what conditions can the sensible world become intelligible? How can it be described? These questions arise from the conviction that incessant change cannot be considered true reality and that, in order to become an object of knowledge and discourse, the sensible world must present, in its very change, something that does not change, something that presents true permanence and is therefore found, in all cases, to be identical. The hypothesis of the existence of intelligible forms – Ideas – raises two specific problems: that of the participation of Ideas among themselves, and that of the participation of sensible forms in intelligible forms. These problems are set out in Parmenides; to resolve the first, a solution is proposed in the Sophist, and to answer the second, Plato puts forward two hypotheses in the Timaeus: that of a demiurge, who fabricates or, rather, orders the universe; and that of chōra, the material on which the demiurge intervenes. Insofar as similarity can be defined as identity reduced to certain aspects, sensible things – as mere images of intelligible forms – must have a certain similarity with them and at the same time differ from them; the demiurge guarantees similarity, while chōra explains difference.

A number of predicates, both positive and negative, make it possible to describe the nature of the demiurge: since he is a god – and a god for Plato must be good (cf. Respublica, II) – the demiurge is good (Timaeus, 29 e) and, as such, his intellect directs his action, since in Plato goodness is linked to rationality. This rationality manifests itself in calculation and speech, and is realized in technical work similar to that of various craftsmen; these two traits indicate the dual aspect of the Timaeus, mechanistic and intentional. To achieve his goal, the demiurge sets to work contemplating a model for transforming a material, obeying a number of rules and achieving certain objectives. The whole of the Timaeus is at stake in this artisan metaphor: the demiurge, because he is good, is devoid of “jealousy” (in Greek, phthónos is a term that designates this fear of seeing someone else equal or surpass us in power or any other quality), and undertakes the construction of a world that is as beautiful as possible. However, like any other craftsman, he is not omnipotent, for two reasons: the existence of intelligible forms and that of chōra do not depend on him; moreover, chṓra (which we translate as “material” to avoid the Aristotelian term “matter”), on which he intervenes, passively resists his efforts.

Three requirements, moreover, lead to the hypothesis of chṓra:

- It explains why sensible things are different from intelligible forms, in which they nevertheless participate (ibid., 52 c–d);

- Chṓra is what gives sensible things their place and is a stable receptacle in which sensible things appear and, after a certain time, disappear;

- Finally, it presents a constitutive aspect for sensible things (and Plato makes this clear by using a number of images and metaphors relating mainly to the mother and the nurse).

Chṓra therefore has a dual aspect, spatial and constitutive; in itself, it is devoid of measure and proportion and, conversely, can admit all kinds of measure and proportion. In the Timaeus, it is never described as such, in its pure state; when the demiurge decides to introduce measure and proportion, it already shows traces of the four elements (ibid., 52 d–53 c), agitated by an automatic and somewhat mechanical motion, devoid of order and measure (see below). This principle of resistance is called by Plato anánkē, a term usually translated as “necessity”, but which must be understood as the set of inevitable consequences that in the sensible world impose severe limits on every rational intent. By admitting the persistent presence of necessity in the universe, with which first the demiurge and then the soul of the world (see below) must contend, Plato recognizes that the order presupposed by his cosmological model is bound to remain partial and provisional; it follows that any cosmological explanation is also doomed to remain partial and provisional.

In the sensible world, permanence manifests itself in the following aspects: causality, stability, and symmetry. There is causality if every effect depends on a cause; stability, if the same cause always produces the same effect; symmetry, if this causal relationship remains unchanged despite incessant transformations. This invariance, which can be expressed in terms of mathematical relationships, constitutes in fact the essence of what man comes to know and describe about the sensible world. However, knowledge and discourse that have sensible things as their object are never true; they remain plausible, insofar as they deal with images and not with true reality.

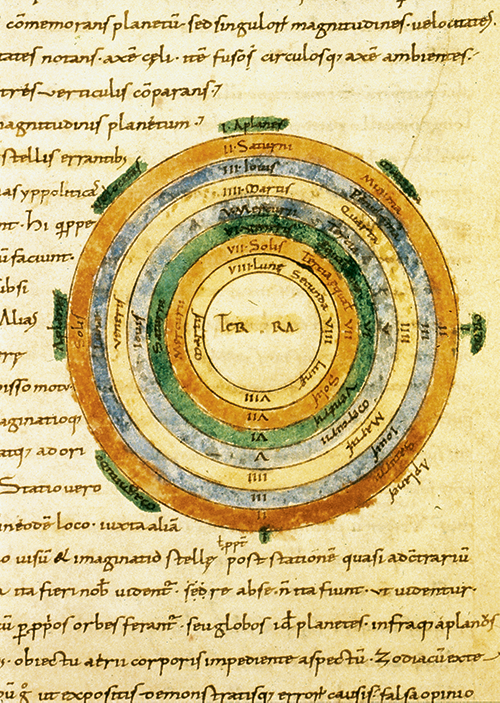

The demiurge, with his gaze fixed on intelligible forms, creates the universe as a living being, endowed with a soul and a body. The body of the world has the appearance of a gigantic sphere, since – as a copy of a perfect original – it must have the most perfect, most symmetrical form, and in three-dimensional geometry, no form is more symmetrical than the sphere.

Why does Plato consider the universe to be a living being, that is, a being endowed with a soul? We have seen that the main problem of his cosmology is to explain what is stable and orderly in the sensible world, which is in constant flux, and above all to explain the most regular movements observed in it, those of the celestial bodies. But how can we explain the origin of these movements and the cause of the order they manifest? To account for the origin and persistence of all movements in the universe – and especially the most noble ones, those that animate the celestial bodies – Plato formulates the hypothesis of a reality that the senses do not perceive: the soul of the world.

In living beings – which, by definition, are endowed with this principle of spontaneous movement that Plato calls “soul” – a certain regularity manifests itself in change: this species generates that species, lives for a certain number of years, has certain characteristics, etc. Moreover, the human soul is endowed with an intellect, which ensures consistent behavior in accordance with certain more or less well-defined intentions. Analogical reasoning allows us to compare these two sets of facts and to suppose that the sensible world is endowed with a soul endowed with reason (Timaeus, 30 a–c), as in the case of man; in light of this assumption, the demiurge begins to fabricate the body and soul of a living being that encompasses all living beings, namely the Universe. The soul of the world, which preserves the order established by the demiurge in the Universe (ibid., 34 c), has the following characteristics: it is an intermediate reality, it has the appearance of an intertwining of circles (the most “noble” of the flat figures, as it has the greatest symmetry), which have mathematical relationships with each other and, finally, it explains every movement, both psychic and physical, in the Universe.

In the Timaeus, the description of the constitution of the soul of the world takes the form of a story that unfolds over time. In doing so, Plato does not violate the postulate formulated in the Phaedrus (245 c–246 a) on the ungenerated nature of every principle, and especially of that principle of ordered movement which is the soul; in fact, the “fabrication” of the soul of the world by the demiurge does not imply an origin in time.

In the description of the mixtures made by the demiurge to fabricate the soul of the world (see tab. 1; Timaeus, 35 a–b), the most general terms of Platonic ontology first appear: Being, the Same and the Other, the great genera evoked in the Sophist (254 d–259 b). The soul has the same essential characteristics as any other reality: being (x exists), identity (x is x, it is what it is) and otherness (x is different from everything that is not x, therefore it is not y, z, etc.). This description merely illustrates two things: on the one hand, the ontological dependence of the soul of the world on the world of Ideas, and on the other, its status as an intermediate reality between this world and the world of sensible things. This intermediate reality represents, in the sensible world, the origin of all orderly movement, the circular movements of the heavenly bodies and the rectilinear movements of sublunary realities. Hence the fact that the Timaeus presents the constitution of the world soul as if it were the manufacture of an armillary sphere, that is, a globe formed by rings or circles representing the movement of the sky and the stars (evoked in Timaeus, 40 d).

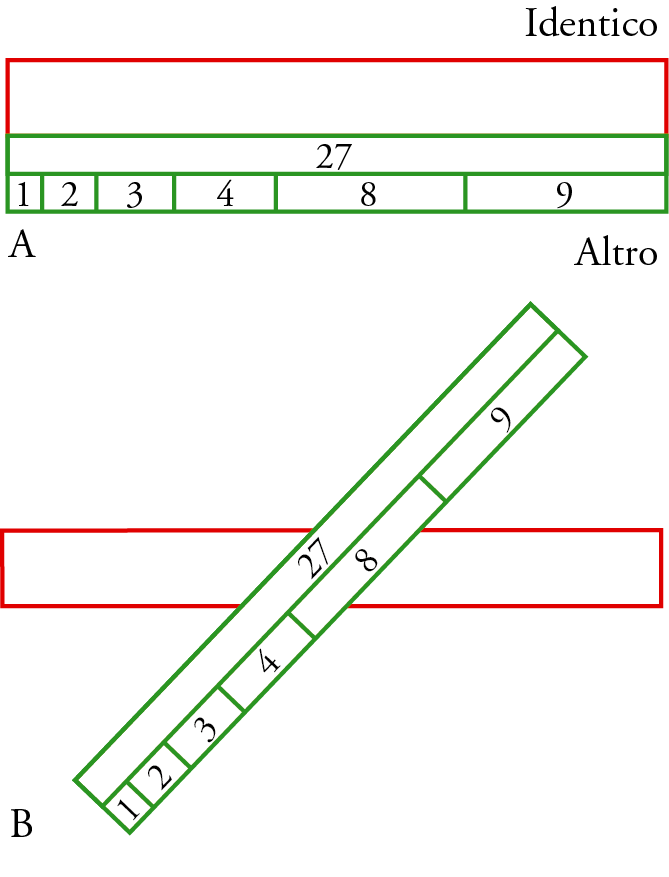

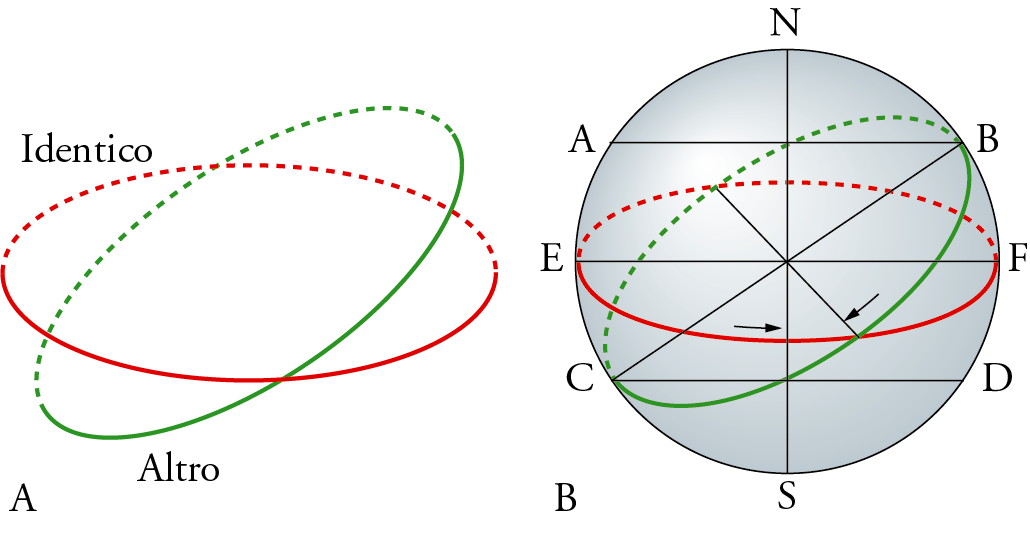

After achieving the fundamental mixture needed to create the soul of the world, the demiurge, working like a blacksmith, laminates this mass to transform it into a plate into which he introduces a number of divisions. He begins by dividing it lengthwise (see fig. 2A) to obtain two strips, which he calls the band of the “Identical” and the band of the “Other” (even though each of them is made up of a mixture of Being, Identical, and Other). The technical operation thus carried out by the demiurge explains, on a metaphorical level, the distinction observed between the fixed stars, which move from east to west, and the planets, which move from west to east: just as the Identical and the Other are two opposites, so the celestial bodies that move on the circle of the Identical (the fixed stars) and on that of the Other (the planets) go in opposite directions. These bands make it possible to construct the two circles on which the celestial bodies will move (permanence is ensured, in a two-dimensional space, by the perfect symmetry of the circle). The demiurge then continues his work by dividing the band of the Other into seven sections, which will allow the creation of the circles on which seven stars will move (the Sun, the Moon, and the five planets known at the time).

However, it is not enough to account for the permanence of the movements of the celestial bodies: their regularity must also be accounted for. This is where “mediation” comes in (the noun, from the Greek mesótēs, in the context in which Plato now finds himself, designates both a set of three terms (A, B, C) and the middle term of this progression, i.e., B). The theory of “mediations” is a priori part of arithmetic and its applications to music: A, B, and C then designate numbers. Interposing a mean B between A and C means dividing the ratio A:C into two ratios A:B and B:C, of which A:C is composed. Three types of mean are introduced, corresponding to the construction of geometric, arithmetic, and harmonic means. These were already used by Pythagoras, according to Giamblichus (In Nicomachi arithmeticam introductionem, 100, 19), but since this is a late testimony, judgment on its validity must be cautious.

The demiurge divides the band of the Other according to intervals given by a sequence of seven numbers: 1, 2, 3, 4, 9, 8, 27, obtained by merging two geometric progressions (i.e., each number is the geometric mean of the previous and subsequent numbers): the first 1, 2, 4, 8 (which produces double intervals, i.e., the distance between two consecutive numbers is two), and the second 1, 3, 9, 27 (which produces triple intervals) (see table 2). Next, working separately on each of the two progressions, the demiurge inserts other numbers between these seven: in each interval, two middle terms that are harmonic means and arithmetic means.

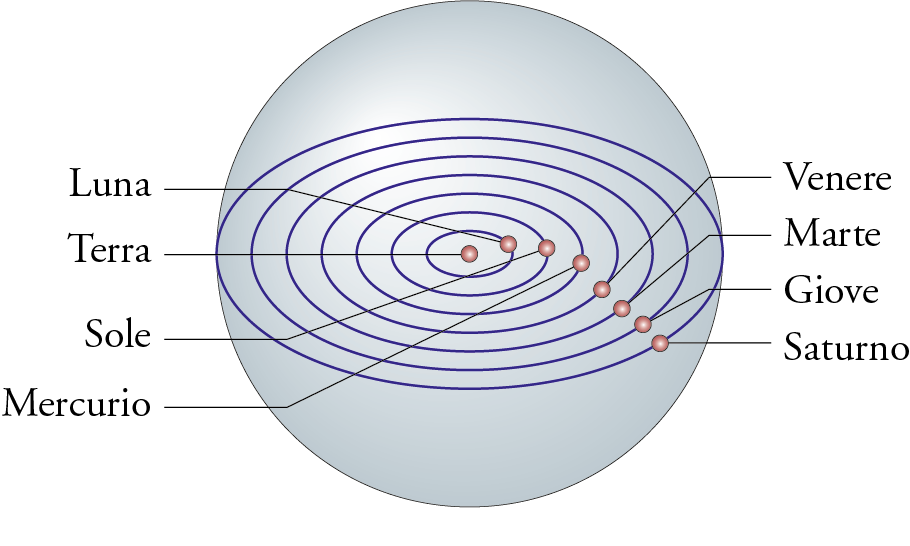

This results in two sequences of ten numbers: in the first (double intervals), the ratio between two consecutive terms is alternately 4/3 and 9/8, and in the second (triple intervals) 4/3 and 3/2. Although this description has some unclear points, it responds to very clear technical considerations. The proportions described apply to a series of positive integers representing the radii of the orbits of each of the seven planets around the Earth: Moon, Sun, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn.

The introduction of “mediocrity” into the soul of the world, which may seem disconcerting, actually fits into the context of an analogical reasoning: Plato seems to want to put the harmony developed from the discovery of musical harmony at the service of astronomy. By applying the same mathematical ratios to material objects, in this case strings of different lengths, we can produce sounds, always the same, which constitute a harmony that is no longer material; in other words, with the help of mathematical ratios that belong solely to reason, we can explain musical sounds, and even produce them, in the sensible world. Why then should it not be the same in astronomy, especially since the movements of celestial bodies display a regularity and permanence that have amazed human beings since ancient times, to the point of making them assimilate them to divinities? To account for these two characteristics, permanence and stability, he formulated two postulates:

- The movements of celestial bodies follow a circular trajectory, their movement is therefore permanent;

- These movements obey laws defined by three types of mathematical relationships known at the time, their movement is therefore regular, despite appearances.

From a strictly musical point of view, the mathematical structure of the soul of the world would comprise four octaves, a fifth, and a tone: \(2/1\times2/1\times2/1\times2/1\times3/2\times9/8=17\); Plato, however, explicitly refuses to theorize what kind of music the celestial bodies could emit, whose motion produces no sound (Timaeus, 37 b).

After separating the plate described above into two parts, the demiurge makes the bands thus obtained coincide in the middle, according to the shape of the Greek letter chi (see fig. 2B). He then curves the two bands into a circle and welds the ends together, thus forming two circles (that of the Identical and that of the Other) inclined towards each other (see fig. 3A): the first, that of the “Identical”, carries from west to east the whole sphere in which the sensible world consists, in addition to the fixed stars, while the second, that of the “Other”, as mentioned above, carries the seven planets known at the time (see fig. 3B). Finally, the demiurge moves on to the last operation, which consists of dividing the revolution of the inner circle six times (Timaeus, 36 d), to obtain seven unequal circles corresponding to the orbits of the planets, while the Earth remains motionless at the center of the sensible world (ibid., 40 b–c) (see fig. 4).

Plato thus arrives at an astronomical system of astonishing simplicity (ibid., 38 c – 39 e). This system involves only circular motion – a hypothesis that will persist until Kepler (law of orbits, 1609) – and takes into account the three types of median ratios (geometric, arithmetic, and harmonic) shown in Table 2.

Plato’s astronomical system considers first of all the motion, both external and internal, of the Universe and the fixed stars. The “external motion” of the Universe, which takes place from left to right, from west to east, and is referred to as the movement of the Identical, communicates an axial rotation to the whole sphere in which the body of the world consists. The “internal motion” of the Universe, which takes place from right to left, from east to west and is inclined on the plane of the ecliptic, is considered as a movement of the Other involving each of the seven planets (the Moon, the Sun and the five planets known at the time, namely Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn); it should be noted that this movement is dominated by that of the Identical, which explains why the sphere of the world always rotates in the same direction. As for the motion of the fixed stars, the Identical communicates to each of them a forward movement, which corresponds to the daily revolution of the star on the celestial vault, and an axial rotation, the latter being due to the action of the soul of the world.

As mentioned above, the Earth is immobile at the center of the Universe (see fig. 4), since the axial rotation of the sphere of the world due to the Identical, in which it participates, is compensated by an opposite axial rotation of which it is endowed. Moving on to the planets, the Identical and the Other each communicate their own movement to each planet, which moves on one of the seven parts into which the band of the Other has been divided; the prevailing motion is that of the Identical, so that the resulting motion of each of the planets gives the impression of a spiral twist; as a group, the planets have a speed equal to that of the circle of the Other and, apart from the Moon and the Sun, they exhibit retrogradations. In particular: the movement of the Moon is accelerated compared to that of the Other; the movement of the Sun is the same as that of the Other; Mercury and Venus exhibit intermittent retrogradations that alter their movement relative to that of the Other; Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn are slower than the Other in that they exhibit retrogradations that drag them in the opposite direction to the other four planets.

The extraordinary complexity of the movements that apparently affect celestial bodies is thus dominated by two mathematical elements: the circle and mediation. It is these two elements that make it possible to construct a relatively simple mechanical model, which helps astronomers illustrate their conclusions. However, it quickly became clear, even within the Academy, that such a simplistic explanation was unable to account for all celestial phenomena.

The demiurge adapts the soul of the world, thus fabricated, to the body of the world (Timaeus, 34 b, 36 d–e). In keeping with a tradition that probably dates back to Empedocles, Plato takes it for granted that the body of the universe was constructed exclusively from four elements: fire, air, water, and earth (56 b–c). But he goes much further; he puts forward a mathematical argument to justify the fact that there must be four elements and, above all, he is aware that he is introducing an important innovation (53 e) by establishing a correspondence between the four elements and four regular polyhedra, that is, by transposing the physical reality in its entirety and the changes that affect it into mathematical terms. The construction of the first regular polyhedra is attributed to Theaetetus (d. 369 or 368 BC), a contemporary of Socrates, whom Plato features in the prologue to a dialogue bearing his name: this shows how attentive he was to the development of mathematics in his time.

In Timaeus (31 b–32 b), Plato first examines the case in which the world has only two dimensions; in such a flat world, three elements would suffice. The reason lies in the fact that between two square numbers there is only one mean term; using modern notation, given two numbers \(a^2\) and \(b^2\), the proportional mean term is \(x=ab\), since \(a^2/ab=ab/b^2\) (e.g., between \(4 = 2^2\) and \(9 = 3^2\), the term is \(6=2\times 3\). But ours is a three-dimensional world. Now, between two cubic numbers, for example \(8 = 2^3\) and \(27 = 3^3\), there are two mean terms: \(12 = 2^2\times 3\) and \(18 = 2\times 3^2\), which can be expressed as follows: given two cubic numbers a³ and \(b^3\), the middle terms are \(a^2 b\) and \(ab^2\), since \(a^3/a^2b = a^2b/ab^2 =ab^2/b^3\). Since the universe in which we live has three dimensions, it must also contain four elements. However, in order to discover these two average terms, it was necessary to use square roots (and cube roots); since the problem of the geometric construction of such quantities had not yet been solved at the time, it is immediately understandable why, a few lines later, Plato writes that the demiurge “placed water and air between fire and earth and in proportional relation as far as possible” (ibid., 32 b).

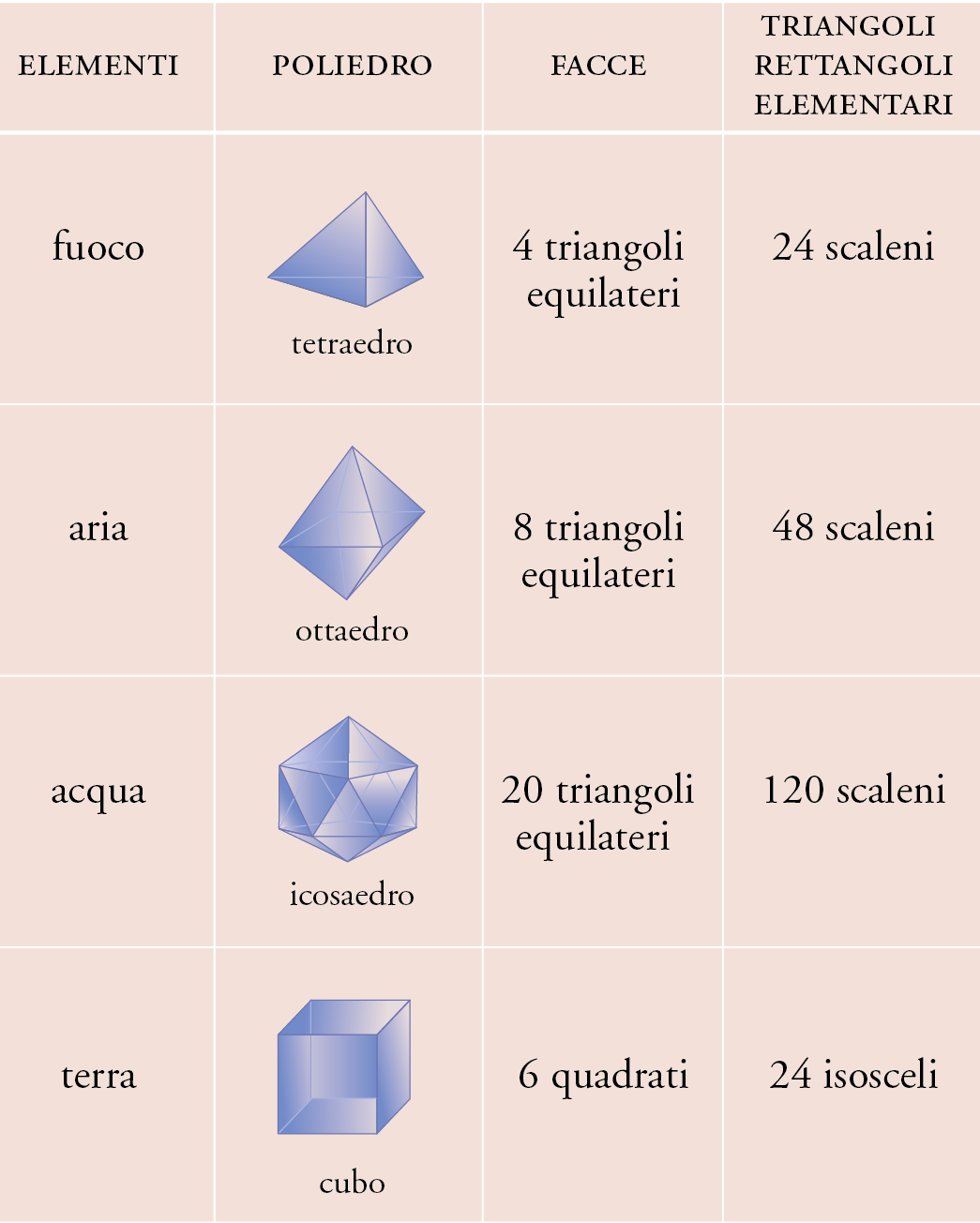

The four elements of which our universe is made (earth, water, air, and fire) are interpreted mathematically by associating fire with the tetrahedron, air with the octahedron, water with the icosahedron, and earth with the cube. The demiurge therefore created the body of the world from perfect geometric bodies, the sphere and regular polyhedra; and the movements and interactions of the polyhedra are governed by mathematical laws, at least where the anánkē has chosen to submit to them.

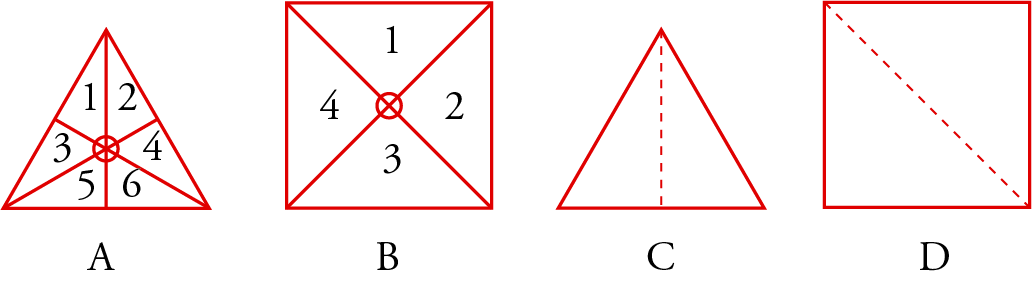

The constitution of the elements. The four polyhedra of the elements are constructed from two types of flat surfaces, the square and the equilateral triangle, which in turn result from two types of right-angled triangles, namely the isosceles right-angled triangle and the scalene right-angled triangle. An equilateral triangle results from the union of six scalene right triangles (54 d–e) (see fig. 5A) and a square results from the union of four isosceles right triangles (55 b) (see fig. 5B); two scalene right triangles would have been sufficient to form an equilateral triangle (fig. 5C) and two isosceles right triangles to form a square (fig. 5D). However, it may be thought that in the case of the square and the equilateral triangle, Plato wanted to find a center of symmetry (cf. Euclid, Elementa, XIII, 18, scholium) such that none of the triangles constituting the square or the equilateral triangle could have preeminence over the others. This could be an implicit criticism of Pythagoreanism, where opposite values were attributed to the left and right.

As shown in Table 2, equilateral triangles are used to construct the tetrahedron (ibid., 54 and 55 a: 4 equilateral triangles), the octahedron (55 a: 8 equilateral triangles) and the icosahedron (55 a–b: 20 equilateral triangles), associated respectively with fire, air and water, while squares are used to form the cube (55 b–c: 6 squares), associated with earth. Finally, there is a brief mention of the dodecahedron, the regular polyhedron closest to the sphere (55 c), a geometric figure associated with the body of the world (see Epistula XIII [apocryphal], 363 d).

The regular polyhedra corresponding to the different elements are therefore described exclusively in terms of the number of faces that make up their envelopes. The length of the edges of the polyhedra can be obtained from the length of the hypotenuse of the elementary right-angled triangles that make up the faces. However, this value remains indeterminate (ibid., 57 c-d), and this indeterminacy is of considerable importance for two reasons: while on the one hand it reduces the explanatory power of Plato’s geometric model by opposing its simplicity, on the other hand it allows for a better account of the varieties of a single element.

Plato wants to show how the cosmological model he proposes allows us to describe the objects of the sensible world, which are varieties of the four elements, or combinations thereof, as well as their properties. The most complex substances found in the universe are ultimately nothing more than varieties of four – and only four – elements (58 c-61 c), which are associated with four regular polyhedra, which in turn are made up of two types of right-angled triangles to which, ultimately, the entire material structure of the universe can be traced back (see Table 3).

Table 3 - The substances of the Universe as varieties of the four elements

| Fire varieties | Air varieties | Water varieties | Earth varieties |

|---|---|---|---|

| The flame that provides light to the eyes | Ether | Fuse | Filtered through water – stone |

| What remains in the bodies that glow | Fog | Adamant | Diamond |

| Other | Darkness | Copper | Not soluble in water – brick |

| Other | Other | Lava | |

| Liquid totally condensed – ice | Soluble in water – nitre | ||

| Hail | Salt | ||

| Half condensed – snow | |||

| Frost | |||

| Not water condensed – juices: | |||

| Wine, oil | |||

| Honey, ferment | |||

| Mixtures of earth and water, fusible under the action of fire – glass | |||

| Wax | |||

| Incense |

The value of this classification lies not in its explanatory capacity but in its function as an illustration of the principle that all sensible reality is reducible to variations or combinations of the four elements.

The correspondences established between the number of equilateral triangles that make up the surface of the polyhedra also allow us to formulate the mathematical equivalences that explain how the four elements transform into one another and how the phenomena of generation and corruption that manifest themselves in the sensible world are produced. Such an explanation is based on the following assumption: the two types of elementary right-angled triangles can neither be created nor destroyed; consequently, the number of triangles of each type involved in a transformation is conserved. Furthermore, only elements corresponding to polyhedra whose faces are formed by equilateral triangles can transform into one another. It follows that water, air, and fire can transform into one another (but not earth, which corresponds to the cube, whose faces are squares) and are the only ones affected by processes of decomposition and recomposition. In short, the transformation of elements is considered in terms of the equilateral triangles (n) that make up regular polyhedra, and not, as would be natural, in terms of volumes (see Table 4).

| Relation | Expression |

|---|---|

| 1 (Fire) | 4Δ |

| 2 (Fire) = 1 (Air) | 2 × 4Δ = 8Δ |

| 1 (Fire) + 2 (Air) = 1 (Water) | 4Δ + 2 × 8Δ = 20Δ |

| 2 ½ (Air) = 1 (Water) | 2 ½ × 8Δ = 20Δ |

This type of solution is surprising, since it only considers the surfaces that limit polyhedra, while polyhedra are volumes. However, it should be remembered that, as we see again in Euclid, what defines a polyhedron is its shape, or its boundary, which corresponds to the set of its faces. On the other hand, the indeterminacy of the length of the hypotenuse of the elementary right-angled triangles that make up equilateral triangles makes it difficult to explain the mutual transformation of those polyhedra whose faces are not made up of equilateral triangles of identical surface area. Finally, the mathematics of Plato’s time encountered considerable difficulties in extracting square roots and found it impossible to extract cube roots.

Irrationality and incommensurability. The extraction of square roots very quickly leads to the problem of quantities that are incommensurable with the unit, a problem that is evoked in Theaetetus (147 c-148 d). The text of this passage is divided into two parts. In the first, very short part, Plato recalls the teachings of Theodore of Cyrene (second half of the 5th century BC) and, above all, the lesson recently given in Athens to a group of young people, including Theaetetus and a young man of the same name as Socrates. The second part develops a limited definition of irrationality based on a classification of integers that distinguishes perfect squares from other numbers, as well as perfect cubes from other numbers.

Theodore addresses the problem of incommensurability both by using an (arithmetic) calculation procedure and by resorting to antinomy (Euclid, Elementa, lib. VII, prop. 1 and 2, and lib. I) or antaneresis (Aristotle, Topica, VIII, 3, 158 b 29-159 a 1), a (geometric) procedure for approximating quantities by successive and alternate subtractions; hence the praise given to him by Socrates, who described him as “the strongest man in calculations and the most profound connoisseur of geometry” (Politicus, 257 a 6-8).

Theodorus proved for the first time – albeit incompletely and using induction – the geometric existence of segments incommensurable with unity, corresponding to the square roots of numbers that are not perfect squares. The equivalence between the arithmetic non-existence of a ratio and the geometric existence of corresponding segments was established at that time for \(\sqrt 2\), as can be seen in Meno (81 a-84 b), and perhaps for other numbers. Theodore does not return to this particular problem, but shows that the equivalence between the arithmetic non-existence of a ratio and the geometric existence of corresponding segments can be established for other numbers, up to 17 or 19 (according to interpretations).

Whatever the role of Plato’s narrative device, one thing remains clear: in a dialogue devoted to science, several works are mentioned that prove the geometric existence of various quadratic irrational numbers. What could have been considered an exception is recognized as the most frequent case. First, a distinction is made between numbers that can be expressed as products of two equal factors (i.e., \(n = a \times a\)) and those that cannot. For solid numbers, i.e., those that can be expressed as the product of three numbers, Teeteto establishes a similar distinction between numbers that can be expressed as the product of three equal factors n = a × a × a (cubic numbers) and those that cannot. And, in the case of all numbers that are not perfect cubes, i.e., \(n=a^2b\), \(n=ab^2\) and \(n = abc\), including prime numbers (which have the form \(n=a\times 1 \times 1\)), if they express the volume of a cube, the edge of the corresponding solid has an irrational measure.

The problem of movement. The limitations described above are real and diminish the appeal of the Platonic cosmological model. This does not mean that the demiurge did not create the universe from the most perfect geometric bodies, the sphere and the four regular polyhedra; that the movements and interactions of these regular polyhedra are governed by mathematical laws (of course, only where the anánkä has been persuaded to submit to this order); and therefore that the body of the Universe is as perfect as possible, given the current state of affairs.

The problem of movement. The hypothesis of the world soul allows Plato to explain not only why and how the movement of the celestial bodies is ordered (see above), but also how and why the movement of sublunar bodies is also subject to mathematical laws; this explains how movement exhibits a certain regularity and permanence. The more the world soul is governed by rigorous mathematical laws, the more the movements of the sensible world will have the possibility of being ordered.

To account for the changes affecting the whole of the sensible world, it is necessary to introduce three principles. First, the universe is not uniform, and the movement observed in it originates from the non-uniformity that reigns there (Timaeus, 57 e). This non-uniformity can be explained in two ways: a weak interpretation justifies it by the fact that there are four regular polyhedra that cannot fit exactly into each other; another, stronger interpretation claims that it results from the fact that the length of the hypotenuse of elementary right-angled triangles remains indeterminate, and it follows that the dimensions of the elementary polyhedra that make up all sensible things may differ. This lack of uniformity is therefore the cause of the incessant change to which the sensible world is subject, a change that the soul of the world attempts to order, but only where it can do so! Secondly, there is no void in the sensible world (58 a, cf. 79 b-c): that is, everything that is must be somewhere (52 b). Finally, the sphere of the world encompasses everything that is corporeal.

The four elements are distributed within this sphere in four concentric layers (33 b, 53 a, 48 a-b) between which exchanges take place. These four concentric layers are involved in the circular movement that animates the whole sphere. Since there is no void, the particles cannot expand infinitely outward; internally, they can only circulate in the interstices that originate from the lack of homogeneity between the elements and are continuously filled. This gives rise to a chain reaction, which is caused by the “compression implied by the process of removal” (58 b, see also 76 c and Leges, X, 849 c) and which causes a process (58 b) in which the two types of movement mentioned above are present, regulating every transformation of one body into another: division and condensation, decomposition and recomposition.

Ultimately, the Platonic universe must be represented as a vast sphere filled with a homogeneous fluid devoid of any characteristics (i.e., chóra), most of which is enclosed in shells that delimit the outer surface of each of the four regular ‘elementary’ polyhedra: tetrahedron, octahedron, icosahedron, and hexahedron. These elementary components tend to divide into four concentric layers, a tendency counteracted by the rotational motion affecting the sphere as a whole. This movement results in the displacement of the regular polyhedra, i.e., a modification of Nature whereby fire becomes air, air becomes water, and vice versa. This representation reveals a contradiction: in the Platonic universe, one must simultaneously take into account the continuous, which must characterize the chóra, and the discontinuous, which is inevitably established by the regular polyhedra. Platonic physics is therefore neither atomism as proposed by Leucippus and Democritus, nor a physics of the continuous as proposed by Parmenides, Zeno of Elea, and Melissus of Samos; it is atomism that develops against the backdrop of a continuous.

Despite this contradiction, it must be admitted that every transformation of one body into another can be explained in terms of mathematical interactions and correlations; the sensible world is in fact dominated by a soul that has a particularly rigorous mathematical structure, and the demiurge has mathematically modeled the chóra by introducing regular polyhedra into it. Mathematics allows us to apply to the sensible world certain predicates of the intelligible world of which it is a part; because of this, the sensible world is thus seen as clothed in permanence and regularity. Ultimately, it is mathematics that accounts for the participation of the sensible world in the intelligible world. If, in fact, the sensible world is an image of the intelligible, then it must be constructed mathematically; in this perspective, it is mathematics that sets the limits of Platonic cosmology.

The soul as the source of life. If biology is understood as the knowledge concerning living beings, we are confronted with a number of difficulties in Plato’s thought. For Plato, indeed, a living being is defined as one endowed with a soul – the soul being the principle of all spontaneous motion, both physical and psychic. All souls, in their immortality, are presented as derivatives or fragments of the world soul, whose constitution is described in Timaeus 35a-b (cf. supra, p. ...).

Beings with souls are, however, arranged hierarchically. At the top are the gods and daemons; below them are human beings – men and women – and animals living in air, on land, and in water; and at the bottom, plants. Therefore, when we speak of biology, a clear distinction must be drawn: humans and animals must be set apart, as they differ both from plants – which possess only a desiring soul – and from the gods (including the cosmos and celestial bodies) and daemons, whose bodies are not subject to corruption. However, in the context of metensomatosis, the distinction between human and animal becomes reinterpreted, since the same human soul – sharing the same structure as that of the gods and daemons – may animate the body of a man, a woman, or even an animal (as defined above), whether it inhabits the air, land, or sea. Consequently, men, women, and terrestrial or aquatic animals are all human beings in origin, all formerly male, subject to a process of degeneration dependent on how they exercised reason in a previous existence.

The human body. Like all living beings, the human being is modeled after the universe (kósmos): he possesses a soul whose rational part mirrors the two circles that compose the soul of the world, governed by the same mathematical proportions; and his body is composed exclusively of the four elements that also constitute the body of the world. Thus, the human being is properly conceived as a microcosm. Yet two fundamental differences distinguish this microcosm from the macrocosm: unlike the body of the world, the human body is perishable; and the human soul undergoes a history, migrating through different bodies depending on the quality of its contemplation of the intelligible, both when disembodied and when incarnate (Timaeus 90e-92c). In general terms, the human being is a compound temporarily uniting a human soul with a body of either male or female sex.

Two fundamental tissues compose the human body: marrow and flesh. To form the marrow, the demiurge selects regular and smooth triangles – those most suited to producing fire, water, air, and earth in their purest geometric form. These triangles are combined to form the marrow, from which the brain, spinal cord, and bone marrow are made. The value of marrow lies in the fact that it provides the anchoring point for the soul’s various species, as will be explained later. The demiurge then sprinkles and washes pure earth with this marrow to create bone, from which he forms the skull, spine, and all other bones.

Next, using elements composed of ordinary triangular surfaces, the demiurge constructs flesh from a mixture of water, fire, and earth, to which he adds a leaven made of salt and acid – also derived from ordinary triangles. As flesh dries, a film forms: the skin. On the skull, moisture pushed out through pores by fire and trapped beneath the skin by air takes root and gives rise to hair. A mixture of bone and unleavened flesh produces tendons, which fasten the bones together. Finally, nails are created from a compound of tendons, skin, and air.

Thus, the human body consists of the four elements, each corresponding to one of the four regular polyhedra, themselves composed of surfaces formed from two types of right-angled triangles: isosceles and scalene. It is the mathematical characteristics of these triangles that account for the difference between marrow – the soul’s anchor – and flesh, a wholly mortal substance. In this framework, biology itself is mathematized, at least at its most fundamental level. The destruction of the human body by disease is likewise described in mathematical terms, as it results from the dissociation or transmutation of its elemental constituents. Death ensues when the marrow – where the soul is anchored – is sufficiently damaged, such that the soul’s bond to the body is loosened and eventually severed.

Three systems – the circulatory (Timaeus 77c-78a), respiratory (78a-80d), and nutritive (80d-81e) – account for the functioning of the human body, which may nonetheless be destroyed by several types of disease (82b-86a). The circulatory system is presented using the metaphor of a garden. First, Plato describes the network of vessels (77c-e) carrying blood throughout the body. Then (77e-78b), he details the movement of blood – produced by the decomposition of food by fire – which serves both to nourish all bodily parts and to act as the medium of sensation.

The respiratory system (78a-80d) is illustrated through the image of a creel: a trap composed of a central fire-filled cavity within the torso and two air-filled funnels passing through the nose and mouth (78a-d). This system operates via an alternating movement that causes the chest to rise and fall, persisting as long as life endures. Air follows fire in a circular motion – entering through the nose and mouth, exiting through the body (78d-79a) – a motion Plato compares to several others (79a-80c). The circularity of these movements is meant to account for their permanence (cf. supra, p. ...).

Finally, the nutritive system (80d-81e) highlights the role of blood, formed by the decomposition of food by fire. The red color of blood comes from this process, and the nourishment is exclusively vegetal. Fire, following air in respiration, dissolves the food in the stomach and forces the resulting blood into designated vessels. This blood, distributed throughout the body, nourishes the marrow, the flesh, and the entire body (80e-81b). Lethal diseases occur when inadequate nourishment causes the marrow – seat of the soul’s species – to degenerate and decay (81b-e).

Diseases that destroy the body fall into three categories. The first includes diseases due to an excess, deficiency, or poor distribution of the body’s elementary components (81e-82b). The second includes those caused by the decomposition of tissues (flesh and sinews), whose liquefaction corrupts the blood (82b-84d). The third encompasses diseases linked to each of the four elements: fevers (86a), diseases of breath (84d-85a), ailments related to phlegm (85a-b), and those associated with bile (85b-86a).

The species of the soul and their bodily localization. As Timaeus reminds us, the soul-species that animate the bodies of living beings – gods, daimones, and humans (at least the immortal part) – are made by the demiourgos from the same mixture that was used to create the world soul, though in a less pure form (Timaeus 41d). Consequently, the immortal species of the human soul can be viewed as a substitute for the world soul. This soul retains the two characteristic circles of the world soul – the circles of the Same and the Other (43e-44b, cf. 44d) – and exhibits the same mathematical divisions governed by proportional laws (43d). Like the world soul, the human soul is the source of motion and knowledge. Its two circles are set in circular motion (42c, 43d; cf. 44b, 44d, 47d, and also 90d). This type of soul performs intelligible cognition and provides the locus for the completion of sensory knowledge (64b). At this level, deliberation emerges as the practical application of intelligible understanding. This species of the human soul – crafted by the demiourgos himself, not his assistants – is immortal (42e, 69c), and therefore divine (69d, 45a); it is a daimōn (90a).

The nature of the mortal species of the soul, by contrast, is less clearly defined. While several passages in Timaeus (69c-e, 70e) affirm its existence, its constitution – entrusted to the demiourgos’ assistants – and its nature are not elaborated. According to Timaeus 69c-d, the mortal part of the soul consists of two subspecies: the irascible part (thymos), responsible for defense and spirited action, and the desiring part (epithymia), responsible for nutrition and reproduction. Thus, the tripartition of the human soul is grounded in a more fundamental bipartition: one immortal species and two mortal ones. The term thymos denotes the warlike aspect of the soul (70a, 90b), whereas epithymia is entirely incapable of comprehending rational discourse (71a, d), not only by disposition (71a) but due to its inherent distance from the immortal, intellectual soul. This vast distance leads Plato to describe the concupiscible soul as a wild beast chained to its feeding trough, bellowing in disorder (70e).

Each soul species is located in a specific region of the human body. The immortal species – corresponding to reason – is situated in the brain. The irascible species resides in the spinal cord at the level of the heart, with which it is closely linked. The desiring species is located in the spinal cord near the liver. In this topographical schema, the brain is assigned preeminence over the heart, a reversal of common medical doctrine in Plato’s time, which typically regarded the heart as the primary organ.

The union of soul and body. The central problem facing the human being – understood as a temporary union of soul and body – is to ensure that the soul governs the body. The immortal species of the soul must remain the “first and best” (Timaeus 42d; cf. 71d), “exercising command” (44d) and securing the obedience of the desiring part with the assistance of the irascible part, which plays an intermediary role. Upon entering a body, the revolutions of the rational soul are disrupted by the influx of sensory impressions, magnified by the movement of the blood that transports them (43c-d; cf. 77e). As a result, birth and childhood represent periods of chaos, during which the rational soul has not yet attained mastery (43a-44b). This marks a fundamental difference from the cosmos, which enters rational life immediately upon the soul’s union with its body. Over time, the situation stabilizes (44b-c), and a temporary cooperation between soul and body is achieved. The privileged site of this cooperation is sensation, or perceptual experience.

The mechanisms of knowledge. What is the mechanism of perception, and more importantly, what is the relationship between perception and rational knowledge in the Timaeus? These are the key questions for anyone interested in Plato’s theory of cognition. The answers offered bear directly on how different types of knowledge about the sensible world are conceived. By emphasizing the physical and physiological processes that make ‘scientific’ activity possible in all its forms, Plato anticipates – albeit partially – the approach of modern experimental psychology.

Perception has two aspects, as it establishes a relationship between a subject – a living being with body and soul – and an external object. Pathémata (the least inadequate translation being “affections”) are not properties residing independently in objects, nor are they, like the sensibilia of the Theaetetus (153a–157a), mere qualities (such as whiteness or blackness) existing only insofar as they are perceived. Rather, they are the effects produced by external objects upon a receptive subject. In the Timaeus (61d–68b), pathémata are systematically linked to the human body as a whole or to one or more of its parts.

In the Timaeus , a distinction is drawn between common sensations, which involve the entire body, and particular sensations, which pertain to specific organs (65b).

-

Whole-body sensations (via touch and the four elements)

- hot/cold (61d–62a)

- hard/soft (62b–c)

- heavy/light (62c–63e)

- smooth/rough (63e–64a)

- pleasure/pain (64a–65b)

- Tongue (taste; associated with water and especially with juices) (65b–66c):

- harsh/sour (65c–d)

- bitter/pleasant (65d)

- pungent (65e–66a)

- acid (66a–b)

- soft (66b–c)

- Nostrils (smell; related to the transformation between water and air) (66d–67a):

- pleasant/unpleasant (66d–67a)

- Ears (hearing; associated with air) (46c–47e; 67a–c; 80a):

- high-pitched/deaf (67b)

- rough/soft (67b)

- high/low (67c)

- Eyes (sight; related to fire) (45b–46c; 67c–68b)

- Elemental composition – Since it contains the same four elements found in plants, blood can interact with any other object composed of these elements.

- Mobility – Its red color signals the predominance of pyr, which makes it highly mobile – an essential quality for any medium of transmission.

- Circulation – Blood moves continuously through the entire body, making it an ever-present conduit for the transmission of impressions from the body to the soul.

- Oceanus: The largest, flowing in the outermost circle – perhaps the shallowest layer. The Mediterranean may be one of its stagnation basins.

- Acheron: Flows opposite to Oceanus, suggesting a conduit on the reverse side of Tartarus. Its lake is Acherousias.

- Pyriphlegethon: Exits Tartarus midway, crosses a fiery region, becoming turbid and molten – thus explaining lava and volcanic eruptions.

- Cocytus: The coldest river, associated with the Stygian realm and the lake Styx, perhaps located closer to the surface.

- Brisson 1974: Brisson, Luc, Le même et l’autre dans la structure ontologique du Timée de Platon. Un commentaire systematique du Timée de Platon, Paris, Klincksieck, 1974 (2. éd. revue et augmentée, Sankt Augustin, Academia Verlag, 1994).

- – 1997: Brisson, Luc, Perception sensible et raison dans le Timée, in: Interpreting the Timaeus-Critias, edited by Tomás Calvo and Luc Brisson, Sankt Augustin, Academia Verlag, 1997, pp. 307-316.

- Bruins 1951: Bruins, Evert M., La chimie du Timée, “Revue de métaphysique et de morale”, 56, 1951, pp. 269-282.

- Cambiano 1971: Cambiano, Giuseppe, Platone e le tecniche, Torino, Einaudi, 1971 (nuova ed. riv. e aggiornata: Roma-Bari, Laterza, 1991).

- Caveing 1982: Caveing, Maurice, La constitution du type mathématique de l’idéalité dans la pensée grecque, Lille, Université de Lille III, Atelier national de reproduction des thèses, 1982, 3 v.

- Cherniss 1944: Cherniss, Harold Fredrik, Aristotle’s criticism of Plato and the Academy, Baltimore (Md.), The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1944.

- Cornford 1937: Plato’s cosmology. The Timaeus of Plato, translated with a running commentary by Francis Macdonald Cornford, London, K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co.; New York, Harcourt, Brace, 1937.

- Dicks 1970: Dicks, D.R., Early Greek astronomy to Aristotle, London, Thames & Hudson, 1970.

- Dombrowski 1981: Dombrowski, Daniel Anthony, Plato’s philosophy of history, Washington (D.C.), University Press of America, 1981.

- Fowler 1987: Fowler, David H., The mathematics of Plato’s Academy. A new reconstruction, Oxford, Clarendon Press; New York, Oxford University Press, 1987 (2 ed.: 1989).

- Hirsch 1997: Hirsch, Ulrike, Sinnesqualitäten und ihre Namen (zu Tim. 61-69), in: Interpreting the Timaeus-Critias, edited by Tomás Calvo and Luc Brisson, Sankt Augustin, Academia Verlag, 1997, pp. 317-324.

- Knorr 1990: Knorr, Wilbur R., Plato and Eudoxus on the planetary motions, “Journal for the history of astronomy”, 21, 1990, pp. 313-329.

- Krämer 1994: Krämer, Hans Joachim, Die Philosophie der Antike, in: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, Basel, Schwabe, 1983-; v. I.4: Die hellenistische Philosophie, 1994, pp. 1-174.

- Lloyd 1991: Lloyd, Geoffrey Ernest Richard, Plato on mathematics and nature, myth and science, in: Methods and problems in Greek science, Cambridge-New York, Cambridge University Press, 1991, pp. 335-351.

- Miller 1962: Miller, H.W., The aetiology of disease in Plato’s Timaeus, “Transactions and proceedings of the American philological association”, 93, 1962, pp. 175-187.

- Müller 1975: Müller, Carl Werner, Die Kurzdialoge der Appendix Platonica. Philologische Beiträge zur nachplatonischen Sokratik, München, W. Fink, 1975.

- O’Brien 1984: O’Brien, Denis, Theories of weight in the ancient world. Four essays on Democritus, Plato, and Aristotle. A study in the development of ideas, Paris, Les Belles Lettres; Leiden, E.J. Brill, 1981-1984, 2 v.; v. II: Plato, weight and sensation.

- – 1997: O’Brien, Denis, Perception et intelligence dans le Timée de Platon, in: Interpreting the Timaeus-Critias, edited by T. Calvo and L. Brisson, Sankt Augustin, Academia Verlag, 1997, pp. 291-305.

- Pohle 1971: Pohle, W.B., The mathematical foundation of Plato’s atomic physics, “Isis”, 62, 1971, pp. 36-46.

- Pradeau 1997: Pradeau, Jean-François, Le monde de la politique. Sur le récit Atlante de Platon, Timée (17-27) et Critias, Sankt Augustin, Academia Verlag, 1997.

- Skemp 1947: Skemp, Joseph B., Plants in Plato’s Timaeus, “Classical quarterly”, 41, 1947, pp. 53-60.

- Solmsen 1968a: Solmsen, Friedrich, Die Entstehung der Wissenschaften, in: Solmsen, Friedrich, Kleine Schriften, Hildesheim, G. Olms, 1968, 3 v.; v. I, pp. 316-325.

- – 1968b: Solmsen, Friedrich, Greek philosophy and the discovery of the nerves, “Museum Helveticum”, 18, 1961, pp. 150-197; ora in: Solmsen, Friedrich, Kleine Schriften, Hildesheim, G. Olms, 1968, 3 v.; v. I, pp. 536-582.

- – 1968c: Solmsen, Friedrich, Plato and the unity of science, in: Solmsen, Friedrich, Kleine Schriften, Hildesheim, G. Olms, 1968, 3 v.; v. I, pp. 326-331.

- Vegetti 1973: Vegetti, Mario, Nascita dello scienziato, “Belfagor”, 28, 1973, pp. 641-663.

- – 1995: Vegetti, Mario, La medicina in Platone, Venezia, Il Cardo, 1995.

- Vlastos 1975: Vlastos, Gregory, Plato’s universe, Seattle (Wash.), University of Washington Press; Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1975.

-

Organ-specific sensations

From the perspective of the perceiving subject, sensation functions as a form of communication: the property of an object is conveyed through a movement originating externally. This movement is transmitted mechanically from part to part, along a circuit (cf. Timaeus 78b–79a; 80a–b), passing through the whole living being – both body (77d–e; cf. 43b–c) and soul (43c). The final recipient of this transmission is the rational part of the soul. The efficacy and quality of this transmission depend on the nature of the receiver – that is, ultimately, on the predominant element (pyr, aér, hydōr, or gē) in each part of the body.

As Timaeus 55e–56a explains, the elements differ in mobility: fire is the most mobile, followed by air, then water, and finally earth, which is most stable. Consequently, body parts composed mainly of earth – nails, hair, bones (64b–c), and those covered with thick flesh (75a) – are poor transmitters of pathémata, with the notable exception of the tongue, a specialized sensory organ (75a5–6). In contrast, parts where fire predominates, such as the eyes, or where air is prevalent, such as the ears, serve as excellent transmitters (64c).

How is it that movement, whether received by a general or specialized organ (eyes, ears, tongue, or nostrils), is transmitted through the body to the soul? Since the role of nerves in sensory mechanisms was unknown in Plato’s time (only discovered later by Herophilos of Alexandria in the 3rd century BCE), it is the blood that carries sensory information through the body (Timaeus 70a–c). Blood, according to Plato, is a red fluid derived exclusively from plant-based food (cf. 77c, especially 80d–e), broken down and transformed by fire (80c–81a), and primarily intended for nutrition (81a–b). Yet, as Timaeus 42e5–43c7 shows, blood also plays a crucial role in transmitting pathémata.

Blood possesses three features that render it an effective transmitter of pathémata: